A recent document allegedly leaked from the Kremlin accuses the Russian hierarchy of being based upon loyalty, not professionalism. “Accordingly,” the author writes, “the higher the level of leadership, the less reliable information they have.”

This raises some interesting questions: shouldn’t, after all, an organization have an inherent basis in loyalty across the levels of the hierarchy? If so, which is more important, competence (or professionalism) or loyalty?

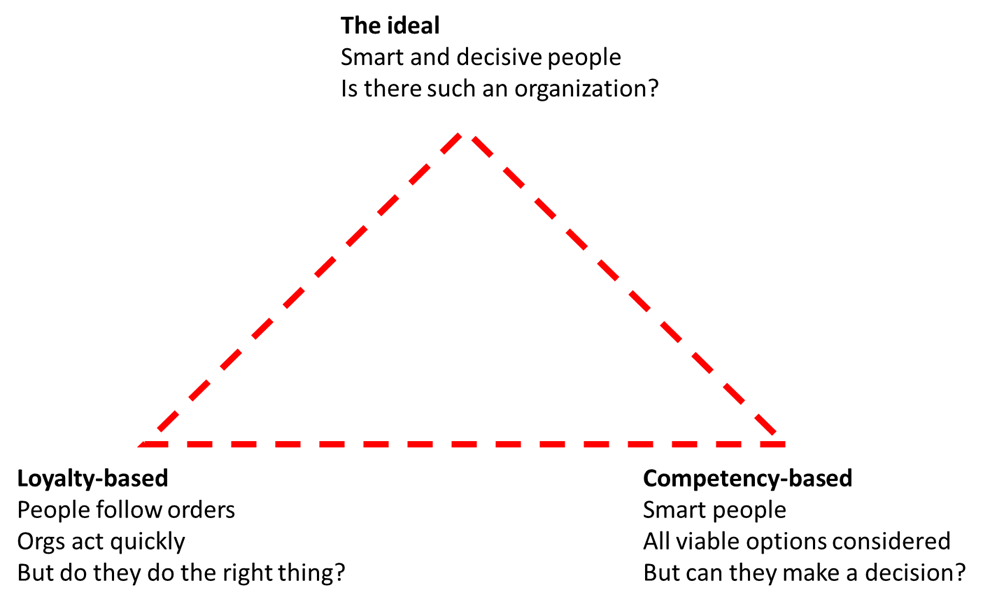

Let’s spend a moment examining this dichotomy. I’ll posit – because I’ve seen them – in business there exist loyalty-centric organizations and competence-based organizations. Each has their merits, but each has serious weaknesses.

The Loyalty-Based Organization

Upon ascending to the American presidency, Donald Trump famously asked his staffers to swear their personal loyalty to him. Whether this was because he felt insecure in his new role, or threatened, or because he had some other motive will likely never be known.

Similarly, in the military, loyalty is a mandate: follow orders or people die.

Every manager wants his or her teams to have some amount of personal loyalty; that’s only human. Loyalty-based organizations take this to an extreme, however: the most loyal get the biggest raises, the juiciest assignments, and so on.

Still, such organizations have advantages. For example, a manager’s wish is followed – quickly – to the letter, which can be very satisfying (for the manager), and such organizations as a result often develop the reputation that they “get things done.”

However, there are some obvious downsides. A manager may hire less competent individuals – or favor them — if he or she deems them loyal, which results in the overall organizational capability to be lowered. Moreover, highly skilled employees will often recognize the existence of a clique – and leave. The work product of such a team will not infrequently be mediocre.

The Competence-Based Organization

At the other end of the spectrum, competence-based organizations place the highest values on skills, knowledge, and professionalism. The driving factor in such organizations is not coming up with an answer, but rather the best answer – often, regardless of how long it takes or whose feelings get hurt along the way.

Competence-based organizations typically seek employees with the highest degrees, with the most accomplishments, but often have trouble keeping them; who wants to stay in a place where analysis takes precedence over accomplishment, where argument is the order of the day? Moreover, what manager wants to stay where employees have no respect or loyalty?

The Ideal

Obviously, organizations should strive for some balance between the two; it’s vitally important for teams to distinguish the relative values of competence and loyalty and strive to create a corporate culture that supports both, one in which healthy, animated discussion of options has its place, in which decisions are made with an open mind – but they are made.

In the real world of course most organizations swing more to one side or the other. As an employee you should know which your organization is; and as a manager, which of the two management styles you’ve created, and perhaps think about making adjustments.

So What Do You Do?

Well, your first decision is do you want to stay in this organization?

Assuming the answer is yes, then if you’re on a loyalty-centric team, it’s probably a good idea to demonstrate loyalty, perhaps by complimenting your boss (“Good idea!”) every now and then, or giving him/her credit (and maybe overdoing it a bit) during a meeting with your boss’s boss — even for one of your ideas! That sort of sucking up can be distasteful, but, hey, you said you wanted to stay.

If you’re in a competence-based organization, put on a program manager hat every now and then and see if you can drive decisions or an action plan (“I see we’ve got just five minutes left in this meeting, what’s the next step?”).

Sometimes, incidentally, what appears to be a competence-based team isn’t really — it’s just that the manager is afraid to take responsibility for a decision. If that’s the case, consider making the decision yourself (assuming you’re okay with the risk). That way the manager can feel comfortable that there’s someone else to point at if things go south (like I say, only if you’re comfortable with taking the responsibility).

Comments are closed.