By Barry Briggs

[This is a draft based on my recollections. I’m sure it’s not complete or even 100% correct; I hope that others who were involved can supplement with their memories which I will fold in. Drop a comment or a DM on Facebook or Twitter @barrybriggs!]

In 1997, Lotus Development, an incredibly innovative software firm that had previously created Lotus 1-2-3, for a time the most popular software application on the planet, and Lotus Notes, for a time the most widely used email and collaboration application, released a set of Java applets called eSuite.

You could say a lot of things about Lotus eSuite: it was, well, very cool, way (way) ahead of its time, and for a very brief period of time had the opportunity of dethroning Microsoft Office from its dominant position. Really. Well, maybe.

But it didn’t.

What went right? What went wrong?

Here is my perspective. Why do I have anything to say about it? Well, I was intimately involved with eSuite. You might even say I invented it.

Java and Platform Independence

In the bad old days of application development, you wrote an app in a language like C or C++ (or even assembler) which compiled/assembled to machine code. That code could only be executed by the specific type of processor in the box, like an Intel 80386. Moreover, your code had to interact with its environment — say, Windows — which meant it had to call upon system services, like displaying a button or a dialog box.

If you wanted to run your code on a different architecture, say a Motorola 68000-based Mac, you had to make massive changes to the source, because not all C compilers were alike, and because the underlying services offered by Windows and Mac were quite different. You coded a button on Windows very differently from one on MacOS or X-Windows. Hence at Lotus we had separate, large teams for Windows, OS/2, and Mac versions of the same product. (In fact, we were occasionally criticized for having spreadsheet products that looked like they came from different companies: the Mac, OS/2, and Windows versions of 1-2-3, built to conform to those platforms’ user interface standards, did look very different.)

Back to our story.

In 1995, Sun Microsystems released the first version of their new high-level programming language, Java. As the first language to compile to byte codes, instead of machine code, it had huge promise because, the theory went, you could “write once, run everywhere.” In other words, each platform – Windows, Mac, Sun, Unix (Linux was still nascent) – would have a runtime which could translate the byte codes to executable code appropriate for that device.

Perhaps even better, Java’s libraries (called the AWT, or Abstract Window Toolkit) also “abstracted” (wrapped) the underlying operating system services with a common API. The AWT’s function to create a button created a Windows button on Windows, a Mac button on MacOS, and so on.

Cool! So why was this more than just a neat technical achievement?

At the time, Microsoft largely dominated personal computing, and its competitors, principally Lotus and Sun, faced existential threats from the Redmond giant. (I’m not going to spend much time talking about how Microsoft achieved this position. There are many varied opinions. My own view, having worked at both Lotus and Microsoft, and thus having seen both companies from the inside, is that Microsoft simply outcompeted the others.)

In any event, many saw Java as a godsend, having the potential to release the industry from Microsoft’s stranglehold. In theory, you could write an application and it could run on anything you like. So who needed Windows? Office?

Browsers

Even cooler, Marc Andreesen’s Netscape Navigator introduced a Java runtime into version 2 of their browser, which at the time pretty much owned the marketplace. Microsoft’s Internet Explorer followed with Java support shortly thereafter.

Everybody at the time recognized that browser-based computing was going to be terribly significant, but web-based applications – especially dynamic, interactive user interfaces in the browser – were primitive (and ugly!) at best. HTML, was both very limited and extremely fluid at the time; the W3C had only been founded in 1994 and in any event the value of web standards had yet to be recognized. Browser developers, seeking to gain advantage, all created their own tags more or less willy-nilly. A very primitive form of JavaScript (confusingly, not at all the same as Java) was also introduced at this time but it couldn’t do much. And the beautiful renderings that CSS makes possible still lay in the future.

Anyway, Netscape and IE introduced an <applet> tag which let you embed (gulp) Java code in a web page. Sounded great at the time: code in a web page! And Netscape had browser versions for Windows, for Mac, for Sun workstations…you could write an applet and it would magically work on all of them. Wow!

A word on security (also kind of a new idea at the time, not widely understood and – in my view – universally underestimated). A web page could run Java in what was called a sandbox, meaning that it was actually isolated from the various aspects of the platform – the idea being you didn’t want to run a web page that deleted all the files on your PC, or scanned it for personal information.

I’ll have more to say about applet security in a moment.

Enter Your Hero

Somewhere around this time, being between projects, I started playing with Java. I had in my possession a chunk of source code that Jonathan Sachs, the original author of 1-2-3, had himself written as an experiment to test the then-new (to PCs: yes, purists, I know it had been around on Unix for years) C language. (How archaic that sounds today!) I have to say before going forward that Sachs’ code was just beautiful – elegant, readable, and as far as I could see, bug-free.

So I started porting (converting) it to Java. Now Java can trace its roots to C and C++ so the basics were fairly straightforward. However, I did have to rewrite the entire UI to the AWT, because 1-2-3/C, as it was called, was not coded for a graphical interface.

And…it worked!

I started showing it around to my friends at Lotus and ultimately to the senior managers, including the Co-CEOs, Jeff Papows and Mike Zisman, who saw it as a new way to compete against Microsoft.

Could we build a desktop productivity suite hosted in the browser that runs on all platforms and thus do an end-around around the evil Redmondians?

Things Get Complicated

Suddenly (or so it seemed to me) my little prototype had turned into a Big Corporate Initiative. Some of my friends and colleagues started playing with Java as well, and soon we had miniature versions of an email client, charting, word processing based on our thick client app Ami Pro, calendaring and scheduling based on Organizer, and presentation graphics based on Freelance Graphics.

And my colleague Doug Wilson, one of the 1-2-3 architects, came up with a brilliant way to integrate applets using a publish-and-subscribe pipeline called the InfoBus, the API to which we made public so anybody could write a Kona-compatible applet.

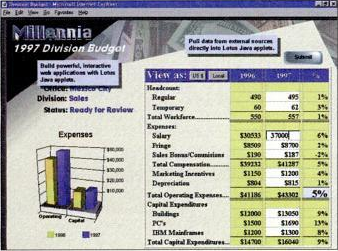

InfoBus was really an amazing innovation. With Infobus we were able to componentize our applications, letting users create what today would be called composite apps. The spreadsheet applet was separate from the chart applet but communicated through the Infobus – giving the illusion of a single, integrated application. So in the screenshot above you see the spreadsheet applet and the charting applet hosted on a web page.

Twenty-five years ago this was pretty awesome.

To make it all official, we had a name for our stuff: “Codename Kona,” we called it, playing off of the coffee theme of Java. (Get it?) Personally I loved this name and wanted it for the official product name…but there were issues. More on this in a moment.

And then a few things happened.

IBM

In June of 1995, IBM (heard of it?) bought Lotus. I heard the news on the radio driving in to our Cambridge, Massachusetts office, and was both horrified and relieved. Lotus – frankly – wasn’t doing all that well so getting bailed out was good; but IBM? That big, bureaucratic behemoth?

IBM purchased the company primarily for Notes, as their mainframe-based email system, Profs, was an abject failure in the marketplace, and Notes, far more technologically advanced, was doing fairly well. And since everybody needed email, owning the email system meant you owned the enterprise – at least that was the contention, and the investment thesis.

To my surprise, IBM showed far less interest in the desktop apps (which we’d named SmartSuite to compete with Office). They couldn’t care less about what was arguably one of the most valuable brands of the time – 1-2-3. But Kona fit into their networked applications strategy perfectly, which (I suppose) beat some of the alternatives at least.

The Network Computer

IBM had another strategy for beating Microsoft on the desktop, and again, Kona fit into it like a glove: the network computer. The NC, in essence, was a stripped-down PC that only ran enough system software to host a browser – no Windows, no Office, everything runs off the servers (where IBM with mainframes and AS/400’s ruled in the data center, and Sun dominated the web).

Oh, my. So we split up the teams: one focused on delivering Kona for browsers, the other, led by my late friend the great Alex Morrow, for the NC.

Lotusphere

Jeff and Mike, our co-CEOs, wanted to showcase Kona at Lotus’ annual developer convention, Lotusphere, held every winter at Disney World in Florida, at the Swan and Dolphin auditorium. Ten thousand people attended in person. (Hard to imagine these days.)

Including, by the way, the CEO of IBM, Lou Gerstner, and his directs.

We had great plans for the keynote address. We developed a script. We hired professional coaches to help us learn the finer points of public speaking. We rehearsed and rehearsed and rehearsed. Larry Roshfeld would do a brief introduction, then I would do a short demo on Windows, and then Lynne Capozzi would show the same software (“write once run anywhere,” remember?) on an NC.

Things went wrong.

First, my microphone failed. In front of this ocean of people I had to switch lavaliers: talk about embarrassing! (These days I tell people I’ve never been afraid of public speaking since; nothing that traumatic could ever happen again!).

But that wasn’t the worst.

In front of all those customers and executives, the NC crashed during poor Lynne’s demo. She handled it with remarkable grace and as I recall she rebooted and was able to complete the demo but talk about stress!

Bill and I

Now as competitive as Lotus and Microsoft were on the desktop, there were, surprisingly, areas of cooperation. For a time, the primary driver of Windows NT server sales was Lotus Notes, and so (again, for a very brief time) it behooved Microsoft to make NT work well with Notes.

And so Jeff, me, and several Notes developers hopped a plane – the IBM private jet, no less! – for a “summit conference” with Microsoft.

We spent a day in Building 8, then where Bill had his office. It was not my first time at Microsoft – I’d been there many times for briefings – but it was to be my first meeting with Bill. After several NT presentations he joined us during Charles Fitzgerald’s talk on Microsoft’s version of Java, called Visual J++ (following the Visual C++ branding). I’ll have more to say about J++ in a minute.

This being my space, I asked a lot of questions, and had a good dialogue with Charles. (I had more conversations with him over the years and always found him to be brilliant and insightful; read his blog Platfornomics, it’s great.) At one point, however, Bill leaned forward and pointedly asked, “Do you mean to tell me you’re writing serious apps in Java?”

To which I replied, “Well, yes.”

“You’re on drugs!” he snapped.

Thus ended my first interaction with the richest man in the world.

Launch

Nevertheless, perhaps because of IBM’s enormous leverage in the marketplace, customers expressed interest in Kona and we got a lot of positive press. Many resonated with the idea of networked applications that could run on a diverse set of hardware and operating systems.

And we were blessed with a superior team of technically talented individuals. Doug Wilson, Alex Morrow, Reed Sturtevant, Jeff Buxton, Mark Colan, Michael Welles, Phil Stanhope, and Jonathan Booth were just some of the amazing, top-tier folks that worked on Kona.

Kona.

As we drew closer to launch, the marketing team started thinking about what to officially name this thing. I – and actually most of the team including the marketing folks – favored Kona: slick, easy to remember, resonant with Java.

We couldn’t, for two reasons.

One: Sun claimed, by virtue of its trademarking of the Java name, that it owned all coffee-related names and they’d take us to court if we used “Kona.” I was incredulous. This was nuts! But we didn’t want to go to war with an ally, so…

Two: it turns out that in Portuguese “Kona” is a very obscene word, and our Lisbon team begged us not to use it. We all were forced to agree that, unlike Scott McNealy’s, this was a fair objection.

The marketing team came up with “eSuite,” which, truth be told, I hated. But I understood it: rumor had it that IBM, our new parent, had paid their advertising firm tens of millions of dollars for their internet brand, which centered around the use of the letter “e” — as in eCommerce and e-business. (Hey, this was 1995!) So our stuff had to support the brand. I guess that made sense.

So What Went Wrong?

eSuite was a beautiful, elegant set of applications created by an incredible team of talented developers, designers, testers, product management, and marketers. So why did it ultimately fail? Others may have their own explanations; these are mine.

Microsoft Got Java Right, None of the Others Did

Paradoxically, the best Java runtime – by far – was Microsoft’s. Sun had written a Java runtime and AWT for Windows but it used a high-level C++ framework called Microsoft Foundation Classes (MFC). MFC, which itself abstracted a lot of the complexity of the underlying windowing and input systems, among others) was great for building business apps (it was the C++ predecessor to Windows Forms, for the initiated). But it was absolutely wrong for platform-level code – the AWT on MFC was an abstraction on top of an abstraction: as a result, it was sssslllooowww. Similar story for Apple, and, believe it or not, for Sun workstations.

Microsoft on the other hand rewrote the Windows version of the AWT directly to Win32, in effect, to the metal. Hence it was way faster. And it re-engineered a lot of other areas of the runtime, such as Java’s garbage collector, making it faster and safer. Not only that, J++, as Microsoft’s version was called, was integrated into Microsoft’s IDE, Visual Studio, and took advantage of the latter’s excellent development, editing, and debugging tools – which no other vendor offered.

I attended the first JavaOne convention in San Francisco. Microsoft’s only session, which was scheduled (probably on purpose) late on the last day, featured an engineer going into these details in front of an SRO audience.

I remember thinking: okay, if you want the best Java, use Windows, but if you’re using Windows, why wouldn’t you just use Office?

Security

Now in fairness, the Java team was very focused on security; I mentioned the sandboxing notion that the applet environment enforced, which has since become a common paradigm. They rightly worried about applets making unauthorized accesses to system resources, like files (a good thing), so at first any access to these resources was prohibited. Later, in v1.1, they implemented a digital-signature-based approach to let developers create so-called “trusted” applets.

But that wasn’t all.

In effect, on load, the runtime simulated execution of the applet, checking every code path to make sure nothing untoward could possibly happen.

Imagine: you load a spreadsheet applet, and it simulates every possible recalculation path, every single @-function. Whew! Between network latency and this, load time was, well, awful.

The Network Computer was DOA

So, if you only want to run a browser, and you don’t need all the features of an operating system like Windows, you can strip down the hardware to make it cheap, right?

Nope.

I remember chatting with an IBM VP who explained the NC’s technical specs. I tried telling him that eSuite required at least some processing and graphics horsepower underneath, to no avail. In fact, as I tried to point out, browsers are demanding thick-client applications requiring all the capabilities of a modern computer.

(Chromebooks are the spiritual descendants of NCs but they’ve learned the lesson, typically having decent processors and full-fledged OSs underneath.)

Sun and Lotus Had Different Aspirations

In a word, Lotus wanted to use Java as a way to fight Microsoft on the office applications front. Basically, we wanted to contain Microsoft: they could have the OS and the development tools on Intel PCs, but we wanted a cross-platform applications that ran on Windows and everywhere else — which we believed would be huge competitive advantage against Office.

To achieve that Lotus needed Sun to be a software development company, a supplier – ironically, to behave a lot like Microsoft’s developer team did with its independent software vendors (ISVs) in fact, with tools, documentation, and developer relations teams.

Sun (as best as I could tell) wanted to be Microsoft, and its leadership seemed to relish the idea of a war (the animosity between Sun CEO Scott McNealy and Bill Gates was palpable). Sun couldn’t care less about allies, as the silly little skirmish over naming proved. But it clearly didn’t understand the types of applications we built, and certainly didn’t understand the expectations users had for their apps. Instead Sun changed course, focusing on the server with Java-based frameworks for server apps (the highly successful J2EE).

Perhaps somewhere along the line it made the business decision that it couldn’t afford to compete on both server and client – I don’t know. In any event the decline of the applet model opened the door to JavaScript, the dominant model today.

Eventually, and tragically, Microsoft abandoned Visual J++ and its vastly better runtime. Why? Some say that Microsoft’s version failed to pass Sun’s compliance tests; others, that Microsoft refused Sun’s onerous licensing demands. In any event, there was a lawsuit, Microsoft stopped work on J++ and some time later launched C#, a direct competitor to Java which has since surpassed it in popularity.

ActiveX

Not to be outdone, Microsoft introduced its own components-in-browsers architecture, called ActiveX. Unlike Java, ActiveX did not use a byte-code approach nor did it employ the code-simulation security strategy that applets had. As a result, ActiveX’s, as they were called, performed much better than applets — but they only ran on Windows. But the FUD (fear, uncertainty, and doubt) ActiveX created around Java applets was profound.

Lotus’ Priorities Changed

Lotus/IBM itself deprioritized its desktop application development in favor of Notes, which was believed to be a bigger growth market. Much as I admired Notes (I’d worked on it as well) I didn’t agree with the decision: Notes was expensive, it was a corporate sell, and had a long and often complicated sales cycle. I never believed we could “win” (whatever that meant) against Microsoft with Notes alone.

It was true that early on Exchange lagged behind Notes but it was also clear that Microsoft was laser-focused on Notes, so our advantage could only be temporary.

Someone told me that “Office is a $900 million business, SmartSuite is a $900 billion business, why fight tooth and nail in the trenches for every sale?” My mouth dropped open: why abandon almost a billion-dollar revenue stream? (Office is now around $60 billion in annual revenue, so staying in the game might have been good. Yes, hindsight.)

eSuite Was Ahead of its Time

Today, productivity applications in the browser are commonplace: you can run Office applications in browsers with remarkably high fidelity to the thick client versions. Google Docs offer similar, if more lightweight, capabilities.

Both of these run on a mature triad of browser technologies: HTML, JavaScript, and CSS. And the PCs and Macs that run these browsers sport processors with billions of transistors and rarely have less than 8 gigabytes of memory – hardly imaginable in the mid-1990s.

And eSuite depended upon secure, scalable server infrastructure conforming to broadly accepted standards, like authentication, and high-speed networks capable of delivering the apps and data.

All that was yet to come. Many companies were yet to deploy networks, and those that had faced a plethora of standards — Novell, Lanman, Banyan, and so on. Few had opened their organizations to the internet.

eSuite’s Legacy

I hope you’re getting the idea that the era of eSuite was one of rapid innovation, of tectonic conflict, competition, and occasional opportunistic cooperation between personalities and corporations, all powered by teams of incredibly skilled developers in each. The swirling uncertainties of those times have largely coalesced today into well-accepted technology paradigms, which in many ways is to be applauded, as they make possible phenomenally useful and remarkable applications like Office Online and Google Docs (which, I’m told, is now called “GSuite”). In other ways – well, all that chaos was fun.

I wonder sometimes if eSuite might have seen more adoption had Lotus simply stuck to it more. To be fair, IBM, which had originally promised to remain “hands-off” of Lotus, increasingly focused on Notes and its internet successor, Domino; I’m guessing (I was gone by this time) that they saw Domino as their principal growth driver. Desktop apps were more or less on life support.

Still, by the early 2000s the concepts of web-based computing were becoming better understood: the concept of web services had been introduced; PC’s were more capable, and networks standardized on TCP/IP. Who knows?

Timing, they say, is everything.

Comments are closed.