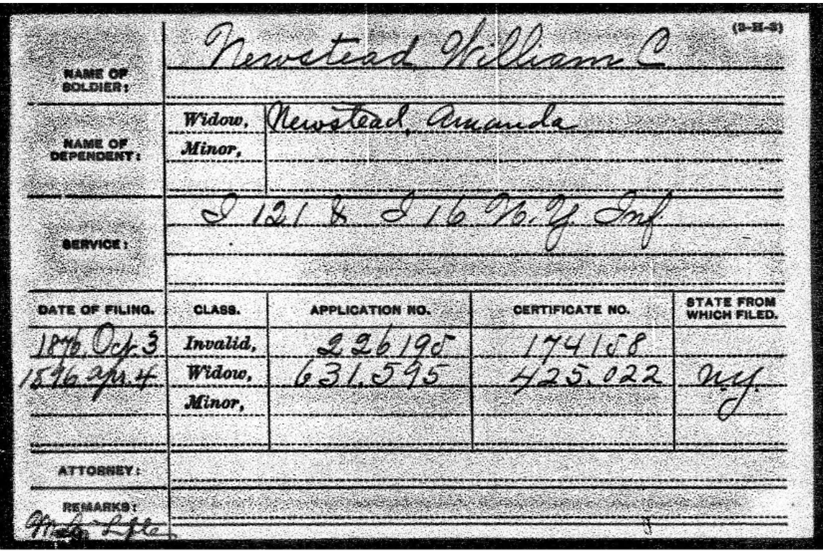

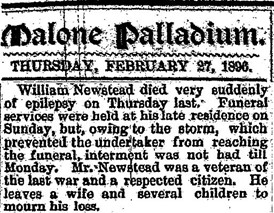

Several people have asked me, being in the software business, how it is possible to use technology to disrupt an election and destroy a democracy.

So, I don’t know for sure. I’ve never done it, never plan to do it (obviously).

But thinking about it, it’s probably not that hard. And as I’ll show later, it’s already happening.

Pretty scary, actually.

What follows is what Einstein called a “thought experiment.” If you (not me) were to do such a heinous thing … well … how would you do it?

And how would you stop it?

First things first, understand the culture

Culture, to paraphrase various great thinkers, trumps everything. So let’s start there.

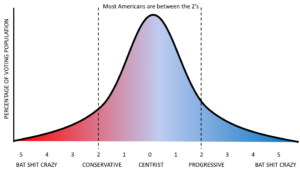

Let’s talk about “red” and “blue” for a moment. Let’s imagine for a moment it isn’t just one or the other, but that there are scales for each. A “red-1” is a moderate that leans Republican, a “blue-2” is generally pretty progressive (say, like Bernie), and “red-5’s” and “blue-5’s” are batshit crazy.

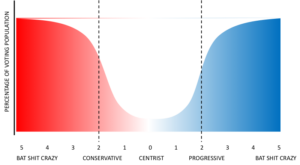

Studies have shown that the overwhelming majority of the American population have until recently fit between the 2’s – more or less in a bell curve, like this:

Which is why we can elect a centrist Democrat president one election, followed by a centrist Republican the following. Clinton was probably somewhere around a “blue-1”, Bush 43 probably a “red-1”, Obama perhaps slightly more liberal than Clinton at a “blue-2” (a totally qualitative assessment by yours truly).

Next: destroy the culture

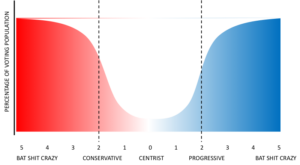

Now, the objective here — and this is important, it’s the core of our strategy – is to take all those 1’s and 2’s and move them further out on the spectrum. Make all the “red-1’s” “red-3’s” or 4’s or 5’s. Ditto with the middle-of-the-road blue-1’s.

In effect, polarize the electorate.

Why? Well, of course “red-1’s” can talk to “blue-1’s”. We’re not that far apart, after all! In fact, you might switch from one election to the next! That’s what swing voters are, after all.

If you’re successful, there will be no more swing voters.

If you’re really successful, America will find itself split down the middle between crazy-ass “red-5’s” and equally nut-job “blue-5’s”.

So what’s the plan? It’s this simple: for every district – and for every precinct, and, yes, it’s possible – for every voter, if they’re red, you want to make them more red – move all the 1’s to 3’s, or even 4’s, or – home run! – 5’s. Do the same for blues.

In short: turn the bell curve into a “well curve”:

This, friends, is the definition of a polarized electorate.

5’s on one side don’t talk to those on the other side like 1’s and 2’s do. 5’s want to beat the crap out of each other. 5’s might compromise with 4’s … but no way with those bastards of the other color!

How do you use technology to radicalize people?

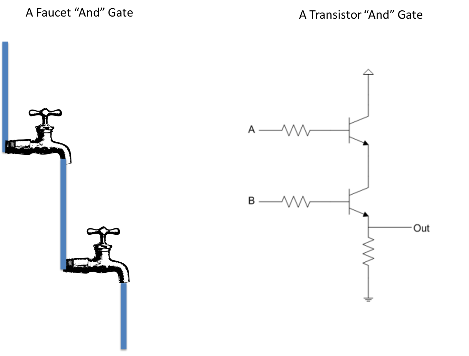

It’s really not terribly difficult, and most of the technology is based on long-proven methods – there’s nothing all that new in the basics. Large companies have used techniques like this for years; every company these days has to have a “Customer Relationship Management” (CRM) system, running on a bunch of servers with customer segmentation, analytics, and predictive modeling (what are you most likely to buy from us next?).

Screwing up a democracy is just an exercise in CRM at scale.

Here’s a rough outline:

-

- Gather your voter data. This is easy, since voter registration data is all in the public domain. Just download it. To your computer wherever you are, which, since it’s the internet after all, could be anywhere on the planet. China. North Korea.

- Now, learn as much as you can about your voters. Again, the basics are pretty easy. You’ll want:

- Historical voting records for each district

- Economic data by district (easy to find on data.gov)

- Crime and other demographic data

This will give you a pretty detailed view district by district. From this, you can start to build a probability for each voter on how they’ll vote. If a district always votes blue, and your voter is in (say) a fairly affluent neighborhood, then there’s a reasonable chance that voter is blue.

But there’s lots of room for error with just this coarse-grained level of information. Your next goal in this exercise is to get very granular with the data: to not just understand area trends, but where a particular individual is on the spectrum. In other words, make that probability a certainty.

Fortunately, there’s lots more data to be gathered!

-

- If you can get credit information, and with the Experian hack, it should all be out there, you can get a pretty good economic view of every single American citizen.

-

- Ditto for military records, union membership records. Hack into church membership lists. You’ll want to target evangelicals in particular with your “make ‘em redder” strategy.

-

- Ditto with political contribution records.

-

- Get college records. Which colleges are liberal and which conservative – this information is well known. If you went to Oral Roberts University, it’s not likely you’re going to vote for Hillary. If you went to UC Berkeley, it is pretty likely. Philosophy majors are more liberal than engineering majors.

-

- Find out people’s habits. Hack into the cable companies and find out what they’re watching. Hannity or John Oliver? Then there’s the ISP’s. What are they searching on?

-

- You can formulate rules, and apply them. Whites in rural areas with low credit scores will vote Republican. Urban women with children are more likely to vote Democratic. In both cases, who knows why, but who cares? Build these rules – hundreds or thousands of them – and test them.

And finally, social media. Deep breath. Yes, Facebook, Twitter, and for that matter, Match.com, GoCupid and the rest.

Let’s take Facebook as an example. Here’s what you (by “you”, I mean either you or your software) do:

-

- For every voter name you have, see if you can find their Facebook page. This shouldn’t be too hard, given you have their name, address, and other information.

-

- See if you can read their posts. Lots of people on Facebook make all their posts public – in which case, you’re done. If not, that is, if they’re actually paying attention to privacy, then friend them.

How do you friend somebody you don’t know?

Make up a name (there are lots of software programs that allow you to synthesize a name; here’s one); find a face somewhere (if trying to friend a male, pick the face of an attractive young woman, and so on; again, there are databases of these things, here’s one); boom, you’re done.

Create a FaceBook (or Twitter, or whatever) profile for your “person.” Using that profile, send friend requests.

- Then write a program to automate this, run it on a few hundred servers, and send friend requests by the thousands in seconds.

-

- Once you’re in, scan the posts for political content. Use sentiment analysis (here’s how, from Google’s AI team) to figure out where your person is on the political spectrum.

Easy.

And no Cambridge Analytica.

Now there’s lots more you could do (and I mean LOTS), but I’m thinking by now you get the idea. At the end of all this you now have a pretty good analysis of every single voter in the United States.

Loose the Kraken

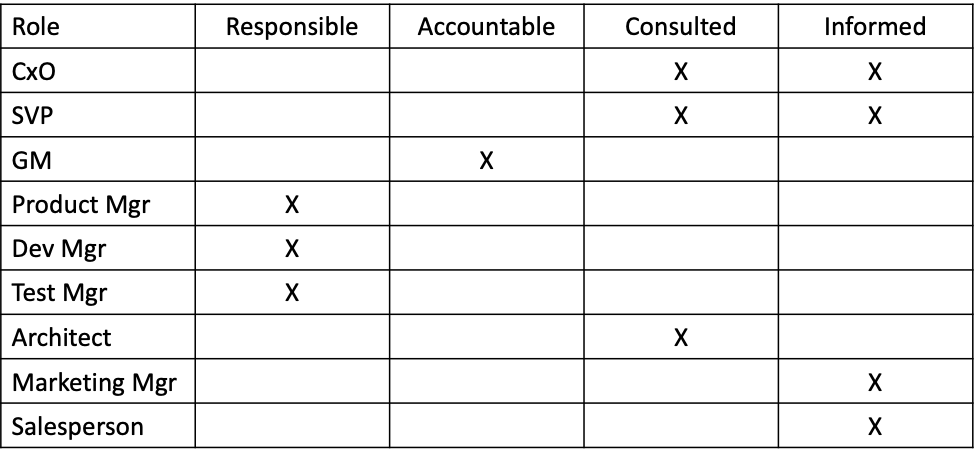

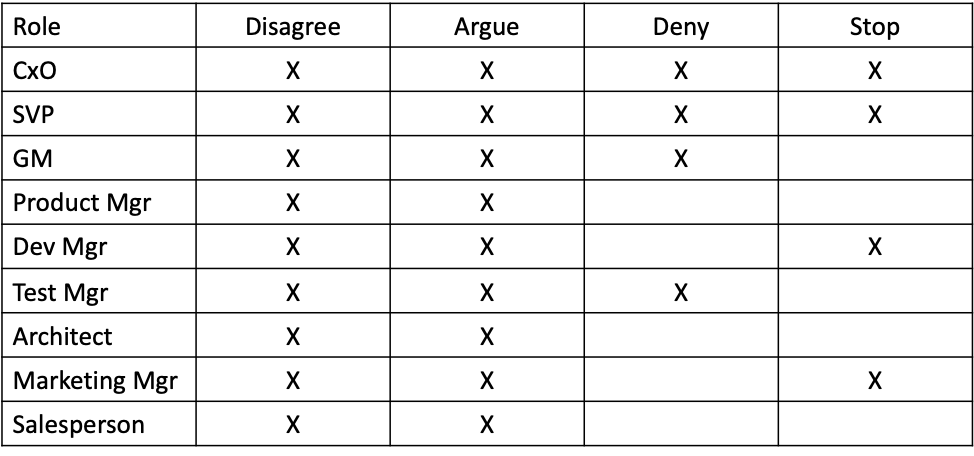

Now it’s time to start the offensive work. In CRM we call these “campaigns,” and we distinguish campaigns as being primarily digital or direct. “Direct” means we send you a physical mail – a brochure, or whatever. Because of printing and postage costs, direct-mail campaigns are falling out of favor.

Digital is cheap, easy, and scales.

First step: hire a bunch of people with basic Photoshop skills. They’re easy to find, cheap, and plentiful. They’ll be your meme-makers.

Second step: provide your meme-makers with design guidelines. They’ll be creating internet memes customized to their recipients. Here are some examples:

| Audience |

Sample Meme |

| Red-1 |

It’s an evil world: prioritize defense spending over social programs |

| Red-2 |

Affordable Care Act is socialism and therefore bad |

| Red-3 |

Immigrants are criminals and Democrats want open borders |

| Red-4 |

Government will imminently impose martial law |

| Red-5 |

“Deep State” is controlled by some mysterious, secretive group |

|

|

| Blue-1 |

Spend more on social programs like schools and health care |

| Blue-2 |

Republicans want to backtrack on civil rights advances |

| Blue-3 |

Republicans want to eliminate Social Security and Medicare |

| Blue-4 |

Republicans support KKK and other radical/racist organizations |

| Blue-5 |

Government is controlled by a secretive group of CEO’s and bankers |

Third step: go through your voter database, and where you see a “Blue-1,” post on their FaceBook page or on their Twitter feed a “Blue-2” meme. Push all the groups over one or two notches.

Fourth step: watch the movement, and repeat the campaigns. Move ‘em!

A Note on Hacking Voting Machines

Well, I mean, you could do it. Apparently, even five-years-olds can.

But that’s not really going to work. It would certainly cause confusion but undoubtedly a technical hack like that would eventually be discovered.

If the overwhelming majority of voters are 1’s or 2’s, on either side, and miraculously a 4 or 5 candidate is elected, somebody’s going to suspect something.

More importantly, you wouldn’t really have effected a cultural change that will take decades to repair.

And then there are hard – and expensive – technical questions, like how many different kinds of voting machines are there, how many versions of the software, how do you clandestinely procure all of them so you can debug and test, how do you test all the variations so that you know they work, how do you deliver the virus if the machines are not connected to the internet, and so on.

If it were me, I wouldn’t bother.

Now, evidently, the Russians did attack voting systems in 2016, My guess however is that this attack was done less to actually change the results and more with the expectation that they would get caught, thus throwing the integrity of the election in doubt.

How Much Would All This Cost?

Like, next to nothing. There are about 235 million people in the US of voting age (according to the University of California, Santa Barbara). So, 235 million records in your database.

So 235 million records, let’s say a megabyte of data per person, that’s like maybe a hundred or so of these puppies.

Maybe – oh, let’s go wild – a thousand servers to hold all the data, for your database, for your Photoshoppers, for development and testing, trial runs, etc. Maybe 500 people working on it. A thousand servers adds up to less than $5 million (you could do it in the cloud for less, and wouldn’t that be grimly ironic, using an American cloud provider to bring down America). 500 folks maybe another $25 million (that’s a very generous $50k/year). So for under $30 million you’ve brought down the greatest democracy in the history of the world.

Sound like a lot?

It isn’t. Netflix (Netflix!) rents tens of thousands of servers every night – tens of thousands — in the Amazon cloud, just to run analytics to predict what you might want to watch tomorrow night.

This is nothing compared to that.

And Russia (just to pick a country at random, okay, not at random) has a total military budget (according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute) in 2016 of around $69 billion. So our little project would be one tenth of one percent.

Basically, that’s discretionary spending.

With a pretty amazing return on investment.

And by the way, make no mistake: this is war, 21st century style. No country will ever challenge the US militarily – that would be suicide – but hostile governments are learning that they don’t have to in order to achieve their objectives vis-à-vis the US.

Von Clausewitz said that warfare is “the continuation of politics by other means.”

What we have here is “warfare by other means.”

Oh, and it’s all 100% totally legal. Chew on that for a second.

Think It’s Nuts?

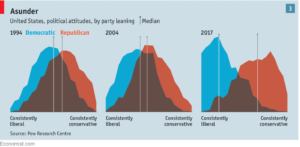

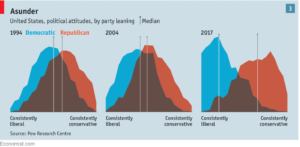

Here’s a study done by the non-partisan Pew Research Center about shifting political attitudes in the US (cited in The Economist, July 14, 2018 issue).

Look familiar?

Look at it: in 1994 and 2004 the majority of Republicans weren’t all that ideologically different from Democrats. But then in 2017: the majority of voters in each party have nothing in common.

Actually it looks exactly like the bell and well curves I showed up at the top of the article!

It’s happening.

Right now.

Scared? You should be.

What’s to be Done?

The situation is not hopeless. There’s lots we can do.

Most immediately, the Good Guys (that’s us) can take steps to counter the Bad Guys’ CRM. We can do the same analysis they’re doing and anticipate the attack.

Both the major parties have large technology organizations that do just this sort of thing: NGP Van for the Democrats, Deep Root Analytics for the GOP. The latter, by the way, just happened to leave all its voter data – on 200 million voters – exposed on the open internet in 2017, in case you thought it would be hard to get this information (and yes, that link goes to Fox News, in case you were worried about liberal media bias).

Both sides are well skilled in CRM skills. I would suggest that the intelligence services be the ones to watch for the onslaught of social media cyberattacks, and then share the data with the parties – both of them, so that both can take whatever action they feel appropriate.

That’s tactical. In the longer term we need to inoculate ourselves against this sort of disinformation, and that can only be done through education. Our kids have to know how to find Korea on a map and how to do long division without a calculator or computer, and they should know in what year the War of 1812 was fought without going to Wikipedia. And they really ought to know that cavemen did not have pet velociraptors. They need to be able to look critically at a meme on Facebook and say, “that’s bullshit.” (The esteemed University of Washington in Seattle actually taught a course on this in 2017. Really: it was called “Calling Bullshit: Data Reasoning in a Digital World,” and it was oversubscribed).

And we need to demand more of the so-called “mainstream media,” on both sides. It’s fine that there’s a left-leaning MSNBC and a right-leaning Fox (actually in my view they’re not leaning, they fell over, but whatever). But too often they either don’t ask the hard questions – of the politicians or of themselves – or they report exaggerations and outright lies in order to get better ratings.

The Great Leveler

The proposed US defense budget for 2019 is $681.1 billion. But using the techniques I’ve outlined, you can cause chaos in any open society for practically nothing. Any country no matter what its GDP can do it. Russia, North Korea, Somalia – as long as they have a pool of reasonably competent technologists (and not that many) they can draw upon.

In a world where it would be the height of insanity for any country to challenge the US military, there are other means.

Winning this information war – and that’s what it is – isn’t going to be easy. But we must: our survival as a democracy depends on it.