This story is about William Charles Newstead who was born around 1834 in the Norwich area of England. Sometime prior to 1840 his father, also named William, brought his family to the United States. They settled in a small town called Burke, New York in Franklin County, in the very far north of New York State on the Canadian border. The industries of the time, besides farming, included “only a grist mill, saw mills, tanneries, asheries, starch factories, brick yards and stone quarries.” We know the rough time of the family’s arrival as the Newsteads are listed on the 1840 Federal Census.

I cannot imagine what brought them to the small village whose population at the time was about 2000 people. (Today it’s less than 300.) Perhaps the Newsteads had friends or relatives already there; or perhaps there were the promises of land grants for new settlers. In any event the Newstead family set up as farmers in the late 1830s. William’s parents no doubt expected to raise their family in this quiet, peaceful town, watch them grow up and then enjoy their grandchildren.

But events were about to take a turn.

On April 12, 1861, South Carolina militia bombarded Fort Sumter, near Charleston, and the island fort surrendered the next day. Thereafter newly elected President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to help put down the incipient rebellion. These recruits were only expected to serve for 90 days, the thinking being that the war against the “bumpkins” in the South would be over very quickly.

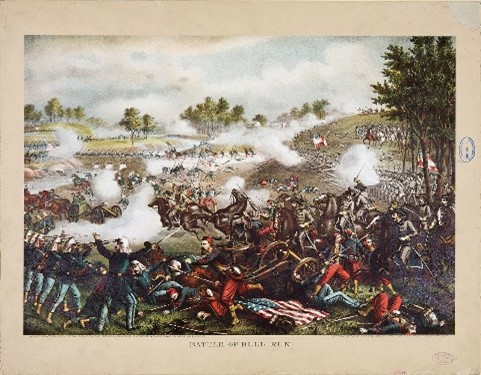

A few months later, on July 21st 1861, when William would have been about 26 or 27, Confederate and Union armies clashed at the Battle of Bull Run, at Manassas Junction in Virginia, heralding the start of the Civil War (or as the South calls it, the War between the States).

At Bull Run, the Union forces were, to the shock of the spectators who had come to witness the event, decisively defeated; both sides recognized that the conflict henceforth would be a protracted affair. Calls for volunteers went up on both sides, and in the North recruitment periods were adjusted to three-year terms.

On September 28th, 1861, young William enlisted in the Union Army and was assigned to the 16th Regiment in one of the three-year recruitments. In those days regiments were defined by the states that they were formed in so William’s regiment was known as the 16th New York. (There were 16th regiments from other states as well.) The 16th New York was composed of volunteers from the most northern parts of New York State, including Franklin County, where Burke is located. Regiments of the time comprised around 1000 men in 10 companies.

William probably underwent training, drilling primarily, for a few short weeks before being sent off to active duty (perhaps according to Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics, the standard work of the time, ironically commissioned by Jefferson Davis in 1853 and published in 1855; Davis, who was Secretary of War at the time, later went on to be President of the Confederate States of America. Hardee himself also joined the Confederate army as a lieutenant general; nevertheless the book was used by the Union as well).

Why did he join? Was it a sense of duty? Was it for the “bounty” (signing bonus) offered? Were all the boys of Franklin County joining up? Or was he an idealist perhaps desiring to help rid the country of the scourge of slavery? We’ll never know.

And the war was over slavery, much as the South for years afterward tried to claim otherwise. Even in the late 1960s when I lived in the Deep South it was still taught in school that the war was about socioeconomic issues or “states’ rights” and not about slavery (a false Yankee claim, they said); such were the textbooks of the time and the prejudices of the place.

Private Newstead joined his unit on October 5, 1861 a member of I Company, commanded by Captain J.J. Seaver, part of the famous Army of the Potomac. (Specifically: “it was assigned to the Second brigade (Gen. H. W. Slocum) of Gen. Franklin’s division. This brigade was composed of the Sixteenth and Twenty-seventh New York, the Fifth Maine, and the Ninety-sixth Pennsylvania, and was not subsequently changed during the period of service of the Sixteenth, except by the addition of the One hundred and twenty-first New York early in September, 1862.”)

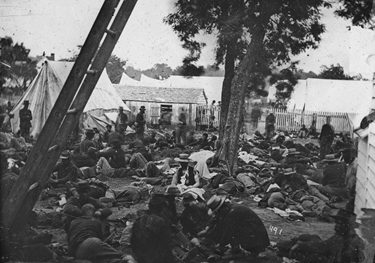

The 16th was known as the “straw hat men” because alone among Union units its troops wore straw hats – a gift apparently from a friend of the regiment.

The regiment overwintered just south of Alexandria, Virginia and did not see action until the spring of 1862. In April 1862 Slocum’s brigade, including the 16th, boarded a ship and sailed to Yorktown to take part in the Peninsula Campaign, an abortive attempt by the Union army to capture the rebel capital at Richmond. On Wednesday, May 7th, 1862, the 16th New York participated in its first battle at Eltham’s Landing (also known as the Battle of West Point) — really more of a skirmish.

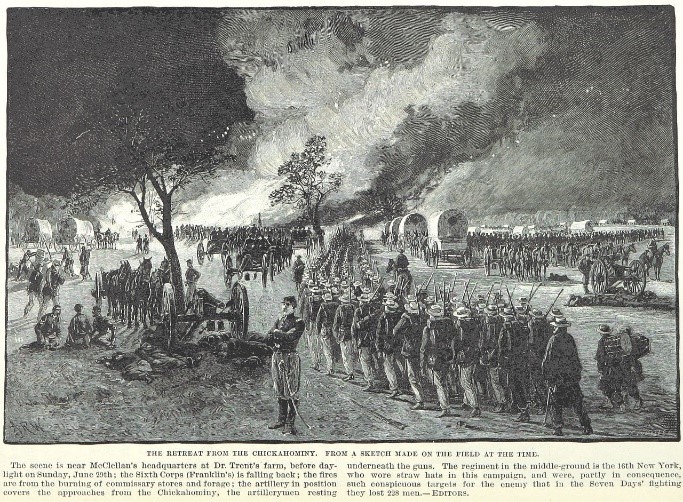

However, on the 27th of June 1862 the 16th New York was heavily engaged at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill — one of the bloodiest battles of the war yet not one of the better known. The Army of the Potomac went up against the bulk of the Army of Northern Virginia under the command of Robert E Lee and the result was a disaster for the Union forces. Private Newstead’s regiment lost about 230 killed, wounded, or missing in that engagement. A few days later, the 16th fought an inconclusive battle at Frayser’s Farm.

What must it have been like, leaving this idyllic village in northern New York State and thrust into the meat grinder where thousands of furious men in one uniform focused on nothing else but the wholesale slaughter of men in the other? Where the wounded lay screaming in the fields, where doctors routinely amputated arms and legs in the most primitive of conditions, and where, after dark, crows, coyotes and wolves feasted upon the human carrion?

Field Hospital at

Savage Station, June 30, 1862, following the battle

(Look closely to see the straw hats)

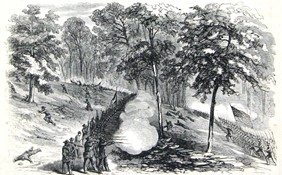

The 16th New York was next engaged at the Battle of South Mountain (Maryland), also known as the Battle of Cramptons Gap, on September 16, 1862. The 16th among other units was charged with dislodging a sizable Confederate force from one of three passes on the mountain. The 16th led the advance – a “brilliant dash” it was called – and suffered 63 killed and wounded.

Battle of Cramptons Gap

History records it thus: “Though the Federals ultimately gained control of all three passes, stubborn resistance on the part of the Southerners bought Lee precious time to begin the process of reuniting his army, and set the stage for the Battle of Antietam three days later,” although the 16th did not participate in that bloody but indecisive battle. Lincoln, claiming a “victory,” announced the Emancipation Proclamation a few days afterwards.

During the mild winter of 1862 to 1863 the division participated in the famous “mud march” in which Union troops attempted to surprise the South by crossing the Rappahannock River; however because of bad weather and disagreements between the Union generals this attack failed.

Following the conclusion of the winter the 16th moved out with the rest of the division and joined General Hooker at Chancellorsville, one of the most important battles of the war and a decisive victory for the Confederates. At that battle, beginning on April 30th — a Thursday – and lasting through May 6th of 1863, the 16th was positioned on the frontline on the right flank. At Chancellorsville the regiment lost 20 killed, 49 missing and 87 wounded.

Perhaps because of the heavy losses it had sustained, the 16th regiment was disbanded later in May of 1863. The so-called “3-year-men,” including William, were transferred to the 121st New York.

The 121st Infantry, under the command of Colonel Emory Upton, was thus known as Upton’s Men. Upton, who subsequently had a distinguished career, rising to the rank of Major General, would later write a book entitled The Military Policy of the United States which shaped American Army policy for decades: arguably, to this day. The 121st was part of the second brigade under Brigadier General Joseph Bartlett, of the First Division led by Brigadier General Horatio Wright who in turn reported to VI Corps, commanded by Major General John Sedgwick.

From June until July of 1863 the 121st was part of the Gettysburg campaign . On the evening of July 2nd 1863, following the heroic defense of Little Round Top by Colonel Joshua Chamberlain and the 20th Maine — perhaps the most decisive engagement of the entire war – the 121st was assigned to reinforce and relieve Chamberlain. It occupied the north end of Little Round Top and held this position until the end of that battle. Two enlisted men were wounded. Thereafter, from July 5th until July 24th to 121st pursued Lee to Manassas Gap Virginia.

Gettysburg was the turning point of the war. Lee, forced to halt his advance into Pennsylvania, began a retreat with his armies to Virginia. Today, on Little Round Top there stands a monument to the 121st .

The 121st, pursuing Lee, subsequently took part in the Bristoe Campaign, a series of bloody battles fought in Virginia during October and November of 1863.

Somewhere in all of these fights young William was wounded, losing a finger. Perhaps because he was no longer able to shoot — it was his right index finger — he was discharged on October 5th, 1863, just short of the full three years. From the gore and agony and horror of the battlefields he returned to quiet Burke, where some time later he married Amanda Esterbrook, an orphan 10 years his junior from the next town over. It’s hard not to wonder how all his wartime experiences colored the rest of his life.

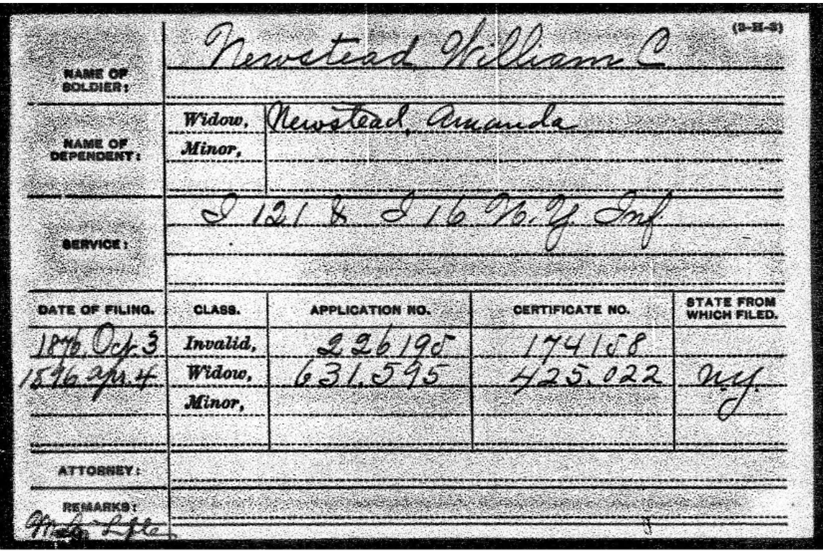

William’s Record in the US Civil War Pension Index

William’s parents were lucky enough to see him return; indeed, they did not pass away until the 1890s. William and Amanda had six children including a daughter, Eva Melinda, who moved to Boston to marry one Patrick Hansbury, in 1893.

Main Street, Burke, New York (date unknown; probably 1920’s)

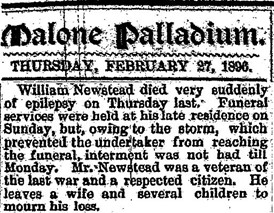

William died in 1896 at age 62 of “epilepsy,” according to his obituary, just a few years after his long-lived parents. After his death Amanda moved to New Hampshire to live with another of her daughters, Emma. Amanda collected William’s veteran’s benefits until she passed away at age 79 in 1922, in Litchfield. She was survived by 18 grandchildren and two great grandchildren.

Eva and Patrick lived in Newton, Massachusetts and had a large family. The eldest, a daughter named Estella, said in later years that her father “treated his daughters like sons, taught them how to do everything.” A stableman, he died in Plymouth in 1924 during a ferocious storm trying to save the horses in his charge (eerily reminiscent of an incident a year prior, when the Newton Journal chronicled the actions of another of Patrick’s daughters, Delia: “Leading ten terror stricken horses through the smoke of a burning stable, Miss Delia Hansbury early Saturday morning saved the lives of every one of the horses belonging to the riding school of her father, Patrick J Hansbury, …”) Eva died in 1939, aged 63, from complications from an appendectomy.

Estella would grow up and marry (on June 10th, 1922, in St Paul’s Cathedral in Boston) Lester Briggs, himself a Purple Heart veteran of World War I and a photo lithographer. They had two children, Wilbur and Kenneth. Lester died of colon cancer in 1946; Estella lived a long and independent life — for years she ran a cosmetics shop in Milton, Massachusetts — passing in 1987 at the age of 92.

Their oldest son, Wilbur, fought as a fighter pilot in World War Two. Upon his return he attended college at Boston University where he met his wife, Elizabeth Bowen. Wilbur and Elizabeth (“Bill” and “Betty”) had two children themselves, Barry and Geoff.

To all the Briggs kids reading: you know the rest; and now you know where you come from – at least one small part of it. Know, as well, that every one of these people I’ve written about is proud of you!

Postscript:

There’s more to our story:

On October 13, 1862, a nineteen-year-old Albany man and immigrant from the Hesse-Darmstadt region of Germany named Valentin Ahlheim enlisted in the 177th New York Infantry “to serve nine months.” The 177th fought in the Western theater of the war, at McGill’s Ferry, Pontchatoula, Civiques Ferry, and “fought gallantly” in the final assault at Port Hudson in Louisiana, the longest siege (48 days, days, called at the time “forty days and nights in the wilderness of death” ) in US military history to that point.

The 177th was mustered out in September 1863; somewhere in this time Valentin was transferred to the 21st Independent Battery NY, which was involved in the same battles; Valentin remained with the unit until the end of the war.

Valentin’s cousin Elizabeth, a few years younger, married an Albany farmer named August Meyer, also a German immigrant. They had seven children; their youngest daughter, Augusta Henrietta, married Albert Edward Bowen on July 10, 1909. Their youngest daughter, Elizabeth, married Estella’s son Wilbur in 1950 – and again, you know the rest.

Images:

Fort Sumter: Currier & Ives, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b49873/ public domain, via Wikipedia

First Battle of Bull Run: chromolithograph by Kurz & Allison, 1880 public domain, via Wikipedia

Straw Hat NY 16th Infantry http://www.framingfox.com/16newyoincp1.html

Retreat from Gaines’ Mill https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/16th_New_York_Volunteer_Infantry_Regiment#/media/File:Retreat_from_Gaines’s_Mill.jpg

Field Hospital at Savage Station VA, June 30, 1862 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/16th_New_York_Volunteer_Infantry_Regiment#/media/File:After_Battle_of_Savage’s_Station.png

Cramptons Gap https://dnr.maryland.gov/publiclands/PublishingImages/SouthMountain_Battle-of-Cramptons-Gap-large.jpg

121st Monument at Little Round Top https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/121st_New_York_Volunteer_Infantry#/media/File:121st_regiment_1.jpg

Burke, NY http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~tollandct01/genealogy/gfentonancestry.html (links on this page are broken but here is the direct link to the photo: http://freepages.rootsweb.com/~tollandct01/genealogy/burkeny.jpg )

William’s Pension Record https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/4654/images/32959_033013-00751?usePUB=true&_phsrc=hwQ403&usePUBJs=true&pId=11890614

William’s obituary, courtesy of Tammy Traster on Ancestry.com https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/5601189/person/316626918/media/d168aaef-778e-4307-9a00-b1306c320175

Muster record for 177th NY: https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/civil/MusterRolls/Infantry/177thInf_NYSV_MusterRoll.pdf Valentin listed on page 82 (about 2/3 down the page). Also see https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/civil/rosters/Infantry/177th_Infantry_CW_Roster.pdf page 1081.

History of the 177th:

https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/civil/infantry/177thInf/177thInfMain.htm