By Barry Briggs

My management coach, a number of years ago, impressed upon me the notion of breakthrough results. If we were planning on 5% growth, then why not achieve 30% growth? 100%? Why limit your thinking to the conventional, to the expected, to the sensible? One might object: that’s hard, would take a ton more work.

What if it doesn’t?

Instead, he suggested, organizations should set themselves goals they might otherwise have thought unrealistic – and then figure out how to achieve them.

Breakthroughs.

We’ve all seen such results: the internet, the iPhone, artificial intelligence. These all represent huge steps forward. The iPhone, for example, did not build on previous mobile phones like the Blackberry or the (godawful) Windows Phone; instead, Apple completely reimagined the product space and invented a whole ecosystem of apps, developers, and marketplace.

Should you swing for the fences?

Well, why not?

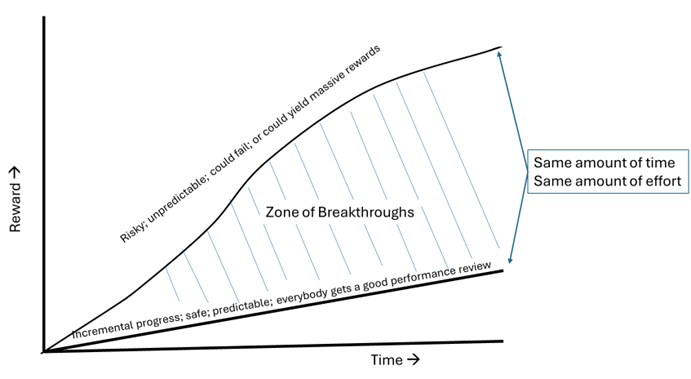

Check out the diagram. Basically, it says that for any initiative, you can either take the incremental route or the breakthrough route.

The incremental route means you carefully plan safe, predictable updates. In software, that means you do point releases: 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and so on. Each release has a small amount of improvements, they’re very predictable in terms of schedule, cost, and time, and, as the chart says, everyone is guaranteed a decent performance review. It’s highly unlikely that any step along the way will fail. (Apple could have made a Blackberry clone and achieved some modest success; but they didn’t.)

The breakthrough route is riskier but yields greater – sometimes much greater – rewards. Breakthroughs “knock over the poker table,” as a friend memorably put it. In a breakthrough-oriented organization, you design nirvana, and then figure out what it will take to get there. There are often many unknowns, problems whose solution is not immediately apparent. You might not understand the market need, or you might even be inventing a new market category; you might not have the resources human or otherwise immediately available; and so on. However, as the iPhone proved, a breakthrough innovation, if you can sleep at night with the risk, can be very rewarding indeed!

But look again at the chart. I’m asserting that breakthroughs and incremental progress can take roughly the same amount of time and effort. It’s really just a question of how much risk and how many unknowns you and your organization can tolerate.

So why not always go for the breakthrough?

Good question. If you had asked me a decade or so ago, I would have said, “right, why not? Swing for the fences! Every time!”

But I am older and wiser now. Organizations – and people – are not always ready for breakthroughs. Caution, even fear, are understandable when individuals are presented with big ideas.

So before you aim for the stars, you’ll have to enroll your team in your vision. They’ll have to buy into it as much as you do and be as invested as you are. Otherwise you’ll just be that wild-eyed revolutionary in the corner – even if you’re 100% right.

That can be hard. Here are some things to think about:

- What’s in it for them? Paint a picture of what life would be like for your stakeholders if they could achieve the breakthrough. If you can get 50% revenue lift instead of 5% how great would that be? You could hire more people, give bigger bonuses, give everyone a company car, perhaps! In other words: enroll your team in your vision.

- Your track record counts. If you’re the new guy with two months on the job, you might not be as successful persuading others as the woman down the hall with ten years’ experience and multiple big-time successes under her belt. What to do in that case? Convince her and let her be the champion.

- Be honest with your team. Lack of honesty or authenticity can kill any initiative, not just the big ones. If at the end of the day it’s really just all about you, sit down. And remember, communication is everything: as breakthroughs are hard, there will be temptations to slow or stop; you’ll need to continuously remind your team of the road they’re traveling. And listen to what they say to you: in a breakthrough project there will be lots of unexpected problems, midcourse corrections, and sudden opportunities. Be a servant leader.

- Be honest with yourself. Are you satisfied that your breakthrough goals are really feasible? Have you done your homework? After all, warp drive or transporters would be wonderful breakthroughs but maybe not possible, at least in our lifetimes. You may not know the answers to all the problems, but you have to have faith in yourself and in your team that the problems can indeed be solved.

- Your organization just might not be ready, for a variety of reasons. Maybe they just came off of a death-march project. Or they’ve had one too many “breakthrough” projects and are suffering from breakthrough “hangovers.” Human nature dictates only so many paradigm shifts per year, or at a time. Change management is hard, time-consuming, and stressful.

So what that means is you need to have your ear to the ground: understand what your team and your organization could be ready for – and perhaps what it’s not.

But at the end of the day: wouldn’t it be better to be standing on the mountaintop, rather than thinking how hard the next day’s climb will be?