By Barry Briggs

“Are we…engineers?”

That was the question I was asked sometime in the late 1970s as I and a colleague carpooled to our offices at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

A true story: back then the profession of software development was so new that people didn’t know what to label us; we didn’t know what to call ourselves, even. Systems Programmer? Applications Programmer? Operator? My official title back then was “Systems Analyst,” whatever that meant. But I was a coder (that word didn’t exist either). I wrote assembly language and FORTRAN for a Univac 1100 mainframe that controlled the first-generation Tracking and Data Relay Satellite (TDRS). Yup.

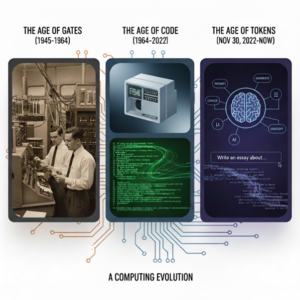

The Age of Gates Gives Way to Code

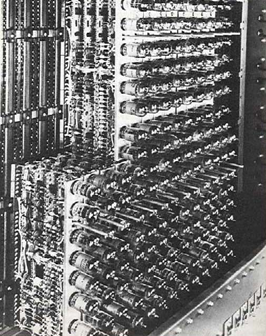

Before that, from World War II through the 1950s, I’ll call the Age of Gates. The majority of computing effort went into understanding and implementing how large numbers of logic gates (AND, OR, XOR, etc.) could be put together in hardware in efficient ways – first with huge banks of vacuum tubes, then with literal magnets, and ultimately with solid-state transistors. (You could open one of the mainframes I worked on back in the day and see the tiny little circular magnets – main memory – painstakingly wired together by human beings.) Concepts like registers, instruction sets, caches, persistent storage, and so on, all had to be invented; and there were countless wrong turns and dead ends along the way.

Early hardware was incredibly unreliable. But eventually the bugs (the word actually comes from a moth caught in an early machine) were worked out, and computers began to proliferate in government and commercial environments. And with them, people to write the early programs.

The Age of Code

Countless software paradigms followed: high-level languages (HLLs) like FORTRAN and COBOL; so-called “structured programming;” object orientation; JIT languages; strongly and weakly typed; aspect-oriented programming; service-oriented architecture; microservices; interpreted languages; compiled languages; transpiled languages; and so on ad nauseum. It’s certainly not a complete list and not all survived the test of time. But I lived through all of them.

And, it’s worth pointing out, no company capitalized on this Age of Code than Microsoft. The Redmond-based company (which quite literally owes existence to the Worst Business Decision in History, when IBM allowed tiny Microsoft a non-exclusive license to PC-DOS, enabling in turn the birth of the PC market…but I digress) recognized that programmers write applications that run on – and thus sell — their OS. Who can forget Steve Ballmer in 1999 shouting “Developers, developers, developers!” on stage, exhorting his company’s core market?

It was a wonderful time. Today, tens of millions of individuals claim the title “Software Engineer.”

And the Age of Code coincides almost exactly with my professional life, from the 1970s until now.

But it is drawing to a close.

The Age of Tokens is Upon Us

We all know what happened on November 30, 2022: ChatGPT was released to the world. Soon it became apparent that Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT and Sonnet and DeepSeek could write code themselves: not good code at first, but after a time, pretty darned good. And today they write emails, compose poetry, plan your day, and offer advice and companionship.

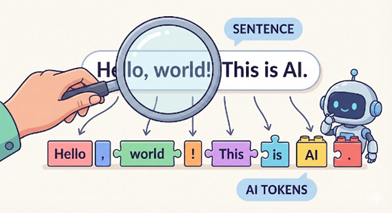

Tokens – just words, syllables, punctuation – are the currency, the fuel for LLMs. LLMs convert your prompts into tokens, process them, and spit them back out as responses, combining them into sentences or code – or tables, music, pictures, or presentations. Increasingly we get computers to do our bidding not by programming in some arcane language but telling them in English what we want them to do. Want an application to handle purchase orders? Or schedule your child’s soccer team practice? Just tell your friendly AI to write the code for you. And then tell another AI to review and improve that code. And another one to write unit tests.

A Gutenberg Moment, and a Sad One at That

It’s a Gutenberg moment in history, when everything changes. “Today there are fewer programmers in the United States than at any point since 1980,” according to the Washington Post.

And there’s no going back.

It’s a bittersweet moment for me, seeing the profession I dedicated my adult life to start to fade away. But – as they say – that’s progress for you.

Still, I’m reminded of a short story the legendary sci-fi author Isaac Asimov wrote all the way back in 1958 entitled “The Feeling of Power” (read it here in the Internet Archive). The main character, a “little man” named Myron Aub, has rediscovered the art of long division by hand, lost as calculators and computers became ubiquitous. Generals, congressmen, even the president, are terrified: “Now we have in our hands a method of going beyond the computer, leapfrogging it, passing through it,” worries a congressman.

As natural language becomes the predominant means of interacting with computers, will we forget programming? Will someone in the distant future “rediscover” how to program a CPU in assembly language? It’s as if, in the last century, we’ve built a new kind of matter, a new Standard Model, or DNA, upon which future generations will add additional layers of unbelievable sophistication, to the point that, maybe a century from now, gates and registers and instruction sets become arcane, and perhaps lost.

I hope they rediscover us, the Coders, as well.

Sources:

3 Ages Diagram and AI Tokens image, me and Google Nano Banana Pro

Vacuum tube memory, Columbia University https://www.columbia.edu/cu/computinghistory/tubes.html

SteveB freaking out, Business Insider https://www.businessinsider.com/steve-ballmers-epic-freak-outs-2015-5#at-another-event-he-got-really-sweaty-while-chanting-developers-developers-over-and-over-2